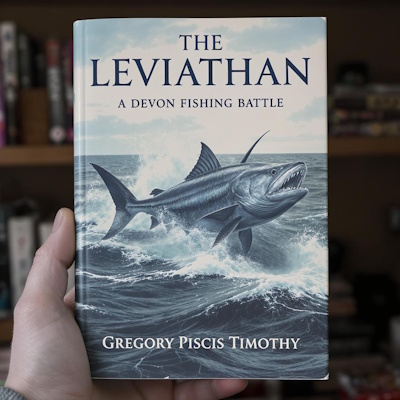

Just like Marlow, following the River Congo, I make my way along the River Tamar and towards the beaches of Devon and into my own Heart of Darkness. After decades of being away from my hometown, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, I have returned, and the pull of the sea is one thing I cannot resist. Azure blue skies meet the deep blue ocean, which in turn gives way to the burning white sands. Unlike in the works of Milton, this is a fishing paradise which shall never be lost to me. With my fishing rod pointed into the air, like the rhongomyniad of the legendary King of Yore, and my tackle box open like a treasure chest from the piratical tales of past centuries, I cast out, ready to face the immense challenge of extracting a leviathan from the deep.

Just as Santiago waited for eighty-four days off the coast of Cuba before his battle with destiny took place, I, too, am thrown into a fishless oblivion for hours that stretch into days. An endless array of white clouds pass by, the wind strengthens and then weakens, and the rain begins to fall, and still the Piscean creatures of the deep fail to materialise. In situations such as this, I, like Nicholas Monsarrat before me, believe the sea can indeed be cruel. And then, just as Mary Shelley’s monster was brought to horrifying life by a strike of lightning, my day bursts into action. The rod tip trembles and then shakes up and down, gently at first and then violently, as a creature of the sea takes my bait and then attempts to make its way back to its deep, dark, dank underwater home. I stand and shout into the sky, “You will not prevail!” but find myself dragged down the beach by the power of the beast, battling and fighting all the way. For me, this could truly be Death in the Afternoon, but unlike the bovine adversary in Hemingway’s masterpiece, mine is an ichthyological foe.

After what seems like an eternity, I eventually gain the upper hand, cranking the reel with fervour, sweat pouring from my brow. Inch by painful inch, I retrieve the line, the fish straining and fighting to remain in its oceanic home. Eventually, I am triumphant, the Jasconius-like creature lying, defeated, on the beach before me. Exhausted by the epic struggle, I slump down onto the golden sands, every ounce of energy I once possessed now expended, my hands raw and blistered, my shirt soaked with sweat, and my mind slipping in and out of consciousness. Because of this, I cannot fully understand what the kindly old man who approaches me says, clearly amazed at what he has just witnessed and deeply concerned for my health after such a gladiatorial conflict. But I can make out the words “undersized”, “below the legal size limit”, “poor cod”, and “I’ll pop that fish back in the sea for you because you could actually be prosecuted for keeping one that small.”

When I awake, it is dark. The fish has gone. Did a beast of such size and power possess the ability to make its way back to its underwater lair? Such an outcome would not surprise me. But I am unconcerned. For me, the glory is in the battle itself, not the spoils of war; the journey is the reason for the quest, not the arrival at the destination. While Alexander may have wept that there were no more worlds to conquer, I, too, allow myself a silent tear, as there are surely no fish more powerful, no fish larger, and no fish more challenging for me to catch.

Gregory “Piscis” Timothy is an award-winning freelance nature writer who specialises in angling. He teaches English Language and Literature with Creative, Descriptive and Expressive Writing at the University of East Anglia where he specialises in Excessive Adverb Use.

Return to The Expert View page by clicking here.