Background

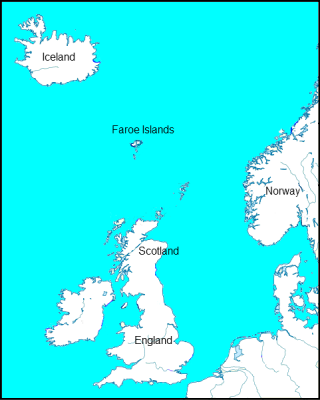

The Mackerel War was a dispute between Britain (backed by the European Union and Norway) and the combined forces of Iceland and the Faroe Islands which began in 2010. Unlike the Cod Wars which was about territory and fishing grounds, the Mackerel War was about the size of catches and quotas that countries are allowed to take from areas where they are permitted to fish. Despite being dubbed the ‘Mackerel War’ this dispute did not see any warships mobilised or direct conflict, as the Cod Wars did. An agreement was reached to bring the Mackerel War to an end in 2014, although there have been several incidents since then which have come close to re-igniting the Mackerel War.

The Cause of the Conflict

In the 1970s and 1980s mackerel had an image problem. People simply didn’t want to eat this species and preferred to stick to more established fish such as cod, haddock, plaice and salmon. But from the 1990s onwards mackerel has become increasingly popular for a number of reasons. Firstly, as it is an oily fish it is full of omega-3 fatty acids which are now seen as offering a range of health benefits. Secondly, it is a very versatile fish with a strong distinctive flavour which can be baked, grilled, barbecued, smoked or even served as sushi or sashimi. Finally, since consumers have largely ignored mackerel for many years its stocks are relatively healthy, making it a good choice for the eco-conscious buyer wanting to avoid the species that are under high commercial pressure. Also, as a pelagic (mid-water) fish it can be caught with fishing methods that do not damage or destroy the seabed environment, making it an even better choice for the environmentally-minded consumer.

The rising value of mackerel has led to the mackerel fishing industry becoming big business – catches in Britain were worth £126 million to Scotland’s commercial fishing sector alone in 2014. Previously, Britain and other European countries such as Norway fished for mackerel, while Iceland and the Faroe Islands were happy to fish for alternative species of blue whiting. However, stocks of blue whiting have sharply reduced in recent years due to overfishing, meaning that Iceland and the Faroe Island’s vast and expensively assembled pelagic trawler fleets have needed to find a new species to catch. These two countries therefore turned their attention to mackerel in a big way – Iceland increased their national annual quota from 2,000 tons in the mid-2000s to 130,000 tons in 2010 and the Faroe Islands increased theirs from 25,000 to 150,000 tons. When combined with the mackerel catch from other countries this would mean that every year 772,000 tons of mackerel were being removed from the sea, 35 per cent more than the 570,000 tons the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas recommends as a safe and sustainable limit. Iceland and the Faroe Islands claimed that global warming meant that mackerel had migrated further north and were more plentiful in their waters which justified the higher quota, and all the additional fishing was within their Exclusive Economic Zone, the area of the sea within 200 miles of their coastline which they have exclusive rights to exploit. This failed to address the fact that their higher quotas were imposed unilaterally and ran counter to the European Union-wide agreements brought in by the Common Fisheries Policy. Many commentators have pointed out that since Iceland was made effectively bankrupt as a country following the 2007 – 2008 world financial crisis it has returned to traditional industries such as fishing, and expanding its pelagic mackerel fishery was a logical next step in this process.

The Conflict Escalates

Britain, Norway and Ireland were furious as – in a very rare example of farsightedness from the commercial fishing industry – mackerel had been caught within safe biological limits and were certified as sustainable by the MSC (Marine Stewardship Council). The massive increases in Icelandic and Faroe Islands quotas would see this sustainability status being removed and the long-term future of the species put at risk. In August 2010 Norway responded by closing all its ports to Icelandic and Faroe Islands trawlers, while similar action was taken at many Scottish ports. This action resulted in the Faroese trawler, the Jupiter being unable to enter Peterhead harbour in Aberdeenshire by a line of Scottish trawlers that blocked the entrance to the port, while several dozen fishermen protested from the land, watched over by a police presence. The Jupiter had been planning on unloading its catch of 1,100 tons of mackerel but was forced to turn around and return to the Faroe Islands. The ship’s skipper Emil Pedersen later claimed that the action had cost him and his company £400,000.

Speaking to the Guardian, Ian Gatt, the leader of the Scottish Pelagic Fishermen’s Association, explained why the action had been taken by the fishermen: “For our guys, it really was rubbing salt in the wound for that boat to come down and say they wanted to land fish in Scotland. Over our dead bodies. … they won’t be getting the famed warm Scottish welcome.” He went on to say that Scottish mackerel quotas could be halved because of the quota increases Iceland and the Faroe Islands had awarded themselves. This would result in thousands of jobs in Scotland’s fishing industry being put at risk, plus all the excess mackerel on the market would drive down the price of mackerel for those who relied on catching the species. Furthermore, the hard-won MSC accreditation would be lost, meaning that consumers would turn away from mackerel, and one of Europe’s few sustainable fisheries would be lost. “Not only us, but everyone who has got the MSC certification is going to lose it – at one stroke” Gatt added.

Talks that followed the Jupiter incident at Peterhead harbour amounted to nothing, while there were high hopes that a three-day meeting in Copenhagen in 2010 between Iceland, the Faroes, Norway and the EU would lead to a resolution but this also ended in deadlock. The situation was then further inflamed with Iceland again upping its quota from 130,000 to 146,818 for 2011. The EU condemned Iceland and the Faroe Islands for further increasing their quotas when the situation between the countries and the EU was already so tense. The EU also warned that Iceland’s bid for full EU membership would be negatively affected by their conduct in the Mackerel War (in the end Iceland decided against joining the EU in 2015). Iceland and the Faroe Islands continued to maintain that mackerel were abundant in their waters and they had every right to set their own catch levels. Iceland also began to ban Scottish trawlers targeting species such as cod and haddock from their waters, meaning that fishermen who had no connection to mackerel fishing were seeing their livelihoods affected by the dispute.

Loss of Marine Stewardship Council Status

In March 2012 the inevitable happened and the MSC announced that any North Sea and North Atlantic mackerel caught after 31st March would no longer be allowed to carry Marine Stewardship Council accreditation. Their reason for this was that mackerel catches would soon exceed 900,000 tons which was at least 260,000 tons over the recommended scientific guidelines. This affected fishing communities in Scotland and northern England, as well as the much smaller and much more environmentally friendly handline fishing industry in south-west England. In addition to this fisheries in Ireland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands would all also lose MSC accreditation for mackerel. In a European fisheries meeting in Brussels in March 2012 the European Commission, under pressure from Ireland and Britain, said it planned to speed up trade sanctions against Iceland due to their “illegal” mackerel catches. Politicians, such as Simon Coveney, Ireland’s Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine stating “This mackerel crisis is about four issues: jobs, economics, sustainability and fairness. The EU cannot accept the Faroe Island’s and Iceland’s unjustifiable and unsustainable fishing of mackerel stocks.”

In February 2013 Iceland agreed to reduce its quota of mackerel from 145,227 tons in 2012 to 123,182 tons in 2013 – a 15 per cent reduction, and also stated that they may be willing to reduce the quota further if other European countries also did the same. However, the EU nations and Norway were unimpressed with this attempted olive branch, with Ian Gatt stating: “[It] is an inescapable fact that Iceland is still taking an excessively large share” and pointing out that even with the 15 per cent reduction in quota Iceland was still taking almost a quarter of the total mackerel catches for itself. Iceland and the Faroe Islands appeared unwilling to back down in their claims to a larger quota of mackerel, while the EU and Norway continued to claim that the unilateral increases of quota were unsustainable and put the whole European mackerel fishery at risk. Sanctions – such as a ban on Iceland and the Faroe Islands landing fish at any EU or Norwegian port and a ban on importing fish products from the two countries – were set to be imposed.

A Partial Resolution

In March 2014 it appeared that the Mackerel War may be coming to some kind of a conclusion. It was reported that a trilateral agreement had been reached that would see the mackerel quota shared in the following way:

- EU Nations & Norway – 72 per cent

- Iceland & Russia – 16 per cent

- Faroe Islands – 12 per cent

A major factor in resolving the dispute was that the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas had revised their assessment of mackerel stocks and found that there had been an increase in the spawning biomass of mackerel and catch levels should not exceed 889,000 tons (compared to the previous 570,000 tons). This effectively meant that there was more mackerel for all countries to catch, and several countries actually saw their quota of mackerel increase under the new agreement. Scotland saw its quota go from 110,000 to 210,000 tons and the new quota given to the Faroe Islands was 6,000 tons higher than the unilateral quota it had given itself which had sparked the initial conflict.

In May 2016 the Marine Stewardship Council announced that North East Atlantic mackerel would have its status as a sustainable species restored, following an assessment period which had taken place over the previous two years. In the Guardian Ian Gatt said that the restoration of the MSC status showed an “unprecedented partnership” between European nations and was a “strong demonstration of the commitment of northern European pelagic fishermen to sustainable fishing and the responsible long-term management of the fishery.”

Ongoing Issues

While the Mackerel War appeared to be over there were still underlying issues which remained unaddressed. The Mackerel War was resolved as higher stocks of mackerel meant that all parties could be kept happy by giving them more mackerel to catch. Any reduction in mackerel stocks would potentially lead to another Mackerel War as nations would battle to retain the large quotas they currently have. In 2019 leaked documents showed that Iceland was planning on increasing its catch of mackerel from 108,000 to 140,000 tons, while Greenland would also increase its catch to 70,000 tons. Russia also planned to increase its mackerel catches in the North Atlantic. This led to an outcry from the European Union and Norwegian fishing industries who accused Iceland and Greenland of once again unfairly increasing their mackerel quotas and risking the sustainability of the entire stock. Iceland (and Greenland) refused to back down even after the threat of EU sanctions was again levelled at the nations, with Icelandic fisheries minister Kristján Freyr Helgason being quoted in the Guardian as saying that the 15.6 per cent of the mackerel quota which Iceland, Greenland and Russia had to share was “nowhere near enough.” This led to the Marine Stewardship Council once again suspending the sustainable status of mackerel in 2019.

In 2023 a coalition of seafood companies and retailers, which included a number of British supermarkets, condemned the countries which fish for mackerel in the North Atlantic for their “collective failure” in agreeing on sustainable quotas. The coalition, which is known as the North Atlantic Pelagic Advocacy Group (NAPA), was set up after MSC status was again lost in 2019. NAPA said that mackerel catches were at least 44 per cent higher than was sustainable which would lead to a stock crash of “potentially epic proportions.” Neil Auchterlonie, the project lead for NAPA, told the Guardian: “This is a collective failure by the coastal states … There is a real frustration around the fact that there is no movement on this.” In an open letter to the EU, Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, the United Kingdom and Russia, NAPA urged all nations to come to a “sustainable and unanimous” agreement on mackerel catches for 2024. They also pointed out that all of these countries had agreed on the total number of mackerel which was sustainable to catch, but the stumbling block came when negotiations began over how to share this quota between nations. At the time of writing [late 2023] the future of North Atlantic mackerel stocks remains uncertain.

This article was originally written in 2014 and updated in 2019 and 2023. Events which have happened after this date will not be reflected in the text above.